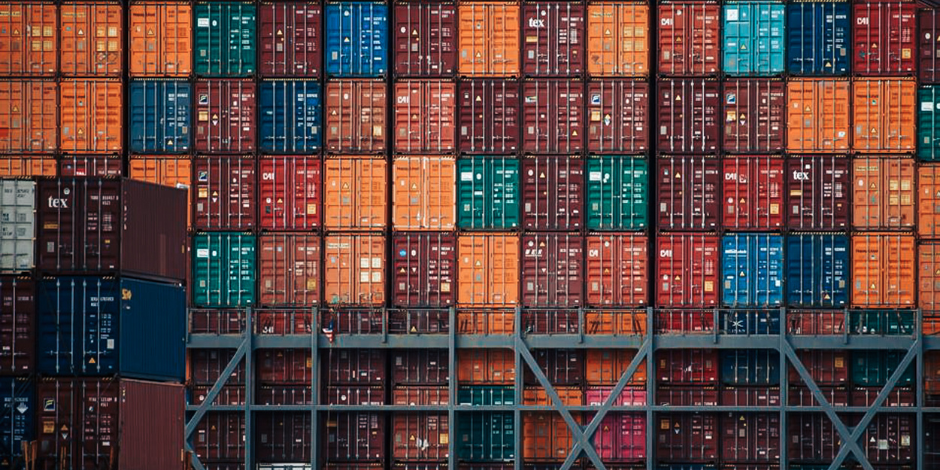

Companies caught between rising import costs and price-shy consumers are accelerating plans to replace Chinese sources.

There’s been a good bit of handwringing within the retail industry lately over how to deal with the federal government’s latest round of tariff increases. The “gift” of inflation triggered by supply chain logjams and funded by the flood of federal stimulus funds early in the pandemic gave retailers the rationale for raising prices. Margins expanded and consumers went on a “revenge” spree.

Now, inflation is the ogre under the bridge and shoppers are not so quick to pull the trigger. This year, major national chains have been “rolling back” prices, mounting big noisy promotions, and waging a war of sorts that consumers have gotten used to and have learned how to exploit.

Shoppers that used to fear “missing out” now patiently wait for and expect promotions and deals.

They have figured out how to flush out the lowest price for the highest value. Thus, the gift of inflation—price flexibility—is being replaced by the sting of eroding margins. In recent conversations with several leading retail executives, all said they expected this year to have to “eat” higher import prices.

It is an election year and, as usual, candidates for federal offices are beating the drums of geopolitics, calling for more tariff increases—to flex our muscles, to show who’s the boss. Tariff policies are also aimed at encouraging home-grown manufacturing sources and the jobs they create, and to discourage potential trade practices that undermine US companies.

For example, China’s automakers have been sitting on a glut of unsold cars. To prevent a plague of cheaper imports that could devastate domestic carmakers, in 2018 the tariff on electric vehicles imported from China was jacked up from 25% to 100%. But tariffs are not so simple.

China is still a major if waning source. China’s share of total apparel imports fell from 34% in 2017 to 22% in 2022, according to research conducted for a group of trade associations. The study found that China’s share of tariff-specific apparel imports fell from 92% to 88%.

Now the pressure is on fashion merchants to speed up the process of pulling more production out of China and re-shoring to countries such as Vietnam, Indonesia, India, and Sri Lanka. Latin America and Central America are often mentioned as obvious near-shoring opportunities, but they are said to lack the necessary infrastructure.

Athletic footwear brand Adidas has been an early mover in re-shoring and rethinking sources. The company announced this summer that its goal is to stop procuring from Chinese sources altogether.

Using tariffs as geopolitical influencers and industry protections sounds like a great idea. But a recent study out of the University of Wisconsin found that the US tariff codes are regressive and favor the luxury market over the mundane—a handbag made of reptile leather has a tariff rate of 5.3%, while a plastic-sided handbag has a tariff rate of 16%.

There is a growing sense of urgency, driven in part by continued overall growth in exports from China to the US and inroads being made by Amazon-like competitors such as Temu and Shein, which can export small orders (less than $800 in value) to the US without any duty. That exemption covers about 70% of Chinese textile and apparel shipments, according to a recent Wall Street Journal report.

As life and commerce spin faster and faster, successful retailers will be those which anticipate the unexpected by evaluating multiple sourcing approaches and the kind of flexibility normally found in the high-tech sector. Another learning from cross-industry observation.

Subscription Required.